There’s nothing sinister about the name “Jesus”. It’s not the Saviors real Name, but it’s not an intentional replacement or a secret insult or sneaky idolatry. “Jesus” is quite simply the sad result of the all too common error called chained transliteration.

Transliteration is properly a transference of sound from one language to another… but only a second language and no more. One to one and done.

And this replication can be done by foreignization or nativization. That is to say, replicating the sound exactly (or as closely as possible), or according to the grammatical rules of the receiving language.

Transliteration should properly only be performed once, from the original language into that of the intended audience. Anything more, creates corruption.

Secondary transliteration results in less accuracy with every step. Each new link in that chain of transliteration makes for loss of information, loss of fidelity, and compounded errors. And this gradual phonetic drift over the branch chain of conversions goes unnoticed by the average individual so that the end result is believed to be the same as the begining.

A lack of understanding of language, translation, transliteration - a basic knowledge of philology - in both teachers and students creates a space for people to make up folly and pass it off as the answers to faith.

“Jesus” doesn’t mean “hail Zeus” as many Messy-anic teachers have touted for far too long knowing little to nothing about language. It doesn’t mean “earth pig” or “earthly swine” either. It doesn’t have anything to do with Dionysus either nor another other demi-god.

The name "Jesus" is simply the natural result of the unnatural process of chained transliteration.

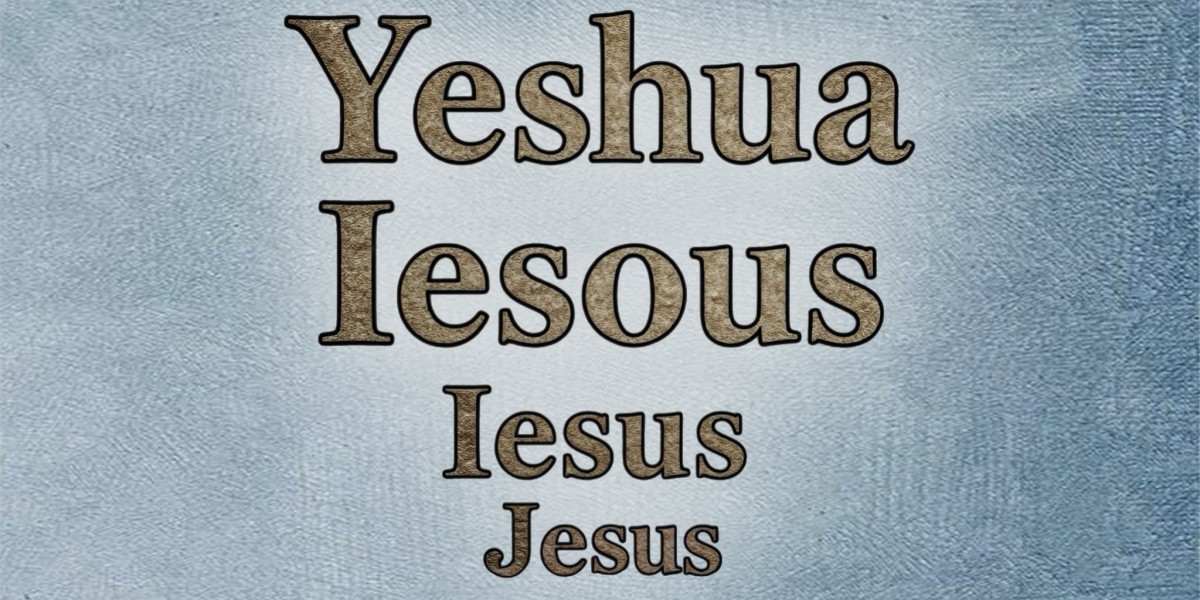

Jesus”” evolved from the Hebrew name "Yeshua" (יֵשׁוּעַ), meaning "salvation."

In the 1st century, the chain began with Yeshua. Yeshua was transliterated into Greek as "Iēsous" (Ἰησοῦς) due to the Greek alphabet's lack of certain Hebrew sounds, like the "sh" sound. Greek also added case endings according to nativization, so "Iēsous" was used in texts like the New Testament.

When the name moved along the chain into Latin, "Iēsous" became "Iesus" because Latin used a similar phonetic structure. (The letter "J" wasn’t common until much later.) "Iesus" became standardized in early Latin texts, like the Vulgate Bible.

By the Middle Ages, the letter "J" emerged in European languages to distinguish the consonant "y" sound from the vowel "i." As vernacular translations of the Bible (like English) appeared, "Iesus" became "Jesus" to reflect pronunciation shifts. The King James Bible standardized "Jesus" in English, aligning with the phonetic and orthographic norms of the time.

In the 1611 King James Version of the Bible, the name appears as "Iesus". This spelling reflects the typographical and linguistic conventions of the time, where the letter "i" was often used interchangeably with "j" in English texts. The name "Jesus" as we know it today became standardized later as the letter "J" gained prominence in English orthography.

The transition from "Iesus" to "Jesus" in the KJV was gradual and tied to evolving English orthography. By the time of the 1769 revision, often associated with Benjamin Blayney’s standardized Oxford edition, the spelling "Jesus" with a "J" had become more common in English Bibles, including updated printings of the KJV. This revision modernized spelling and punctuation to align with contemporary English usage, and "Jesus" likely became standard around this time.

The exact point of transition is hard to pinpoint because various printers made incremental changes, and no single "official" edition marks the switch. By the mid-18th century, "Jesus" was predominant in most English Bibles, including later KJV printings.

The chain was complete and the people bound by it.

Yeshua became Iēsous.

Iēsous became Iesus.

Iesus became Jesus.

And Jesus became backdated as the original.

Not only transliteration but also accent and dialect affected this change.

The influence of French accents, particularly from the Norman noble class after William the Bastard’s Conquest of England in 1066, played a significant role in the eventual development and adoption of the "J" sound in English, though its impact on the transformation of "Iesus" to "Jesus" is more indirect and part of a broader linguistic evolution.

After the Norman Conquest, French became the language of the English court, nobility, and clergy for several centuries. This introduced a significant French linguistic influence on Old English, which was Germanic in structure. The Norman dialect, a variant of Old French, affected pronunciation, vocabulary, and orthography in England, including how Latin was pronounced in ecclesiastical contexts like the Mass.

In Latin, "Iesus" was pronounced roughly as "YAY-soos" or "EE-ay-soos" in classical Latin, with the initial "i" sounding like a "y" (as in German *ja*). In ecclesiastical Latin, the pronunciation shifted slightly but retained a similar initial "y" or soft "i" sound. French priests, influenced by their native phonology, would have pronounced Latin with a French accent, which definitely affected how "Iesus" sounded in religious settings.

In Old French, the letter "i" before a vowel often developed a softer, more palatalized sound, approaching a consonantal "y" or a proto-"j" sound. This phonetic tendency made "Iesus" sound closer to "ZHAY-soos" or "JAY-soos" from the mouths of French-speaking clergy, especially in a liturgical context of the Mass and therefore in the hearing of the English common people.

The "J" sound as we know it in modern English wasn’t fully established in the early Middle Ages. In Latin and early Romance languages, the letter "i" (when used as a consonant) was pronounced as a "y" or, in some contexts, began to shift toward a softer fricative or affricate sound. In French, particularly after the 10th century, this consonantal "i" evolved into the voiced palatal fricative like the modern French "j". This shift was part of a broader phonetic change in Romance languages, where Latin consonantal “i” became a distinct sound.

The Norman French influence on English after the 11th century introduced many French loanwords and pronunciations. While the nobility spoke French, and the clergy used Latin with a French accent, this didn’t immediately change the spelling of "Iesus" to "Jesus." However, it laid the groundwork for the later adoption of the letter "J" in English orthography. The French pronunciation of "i” as a softer, more palatalized sound completely influenced how English speakers heard and eventually pronounced Latin names like "Iesus."

The letter "J" itself began to emerge in European languages during the Middle Ages to distinguish the consonantal "i" from the vowel "i." This was particularly evident in French scribal traditions, where "J" started appearing in manuscripts by the 13th–14th centuries. In English, the adoption of "J" was slower but accelerated with the spread of printing in the 15th century. By the time of the Renaissance, "J" was increasingly used to represent the consonantal sound in names like "Iesus," especially as English pronunciation diverged from Latin and French.

French-influenced scribes and printers, familiar with the French "j" sound, helped standardize spellings like "Jesus" in English texts. The later revisions of the King James Bible cemented "Jesus" with the "J" spelling, reflecting both the orthographic trend and the pronunciation shift influenced by French and other Romance languages. The English "J" sound differed from the French, but the French accent contributed to the perception of "Iesus" as having a distinct initial consonant sound, paving the way for the "J" in spelling.

+

So, while Jesus isn’t a pagan name, a secret satanic replicant, or anything to do with the Greco-Roman deities, it is definitively not the real Name of our King Messiah.

Is it evil? Not necessarily, no. Not unless that last rendition of His Name run through those linguistic jumble of jargon and revisionism is set up as His True Name. Then it is most definitely evil. Then it is creating a replacement based on our own cultural devising and deifying the work or our own imagining.

“Jesus” is not pagan but neither is this name holy. It is simply the bones of the once living body, the carcass remaining from the linguistic buzzards’ banquet.

“Jesus” is a leftover. It is the remains. Not sacred. Just common.

Not right. Not wrong. Just what is…a corpse of a once living thing to which we have been chained by transliterated tradition.

Can we escape this chain and return to the living holy thing we once had? Absolutely….All it takes is a choice.

Second Guess First Assumptions

Question Everything

Get Biblical