Watch

Events

Articles

Market

More

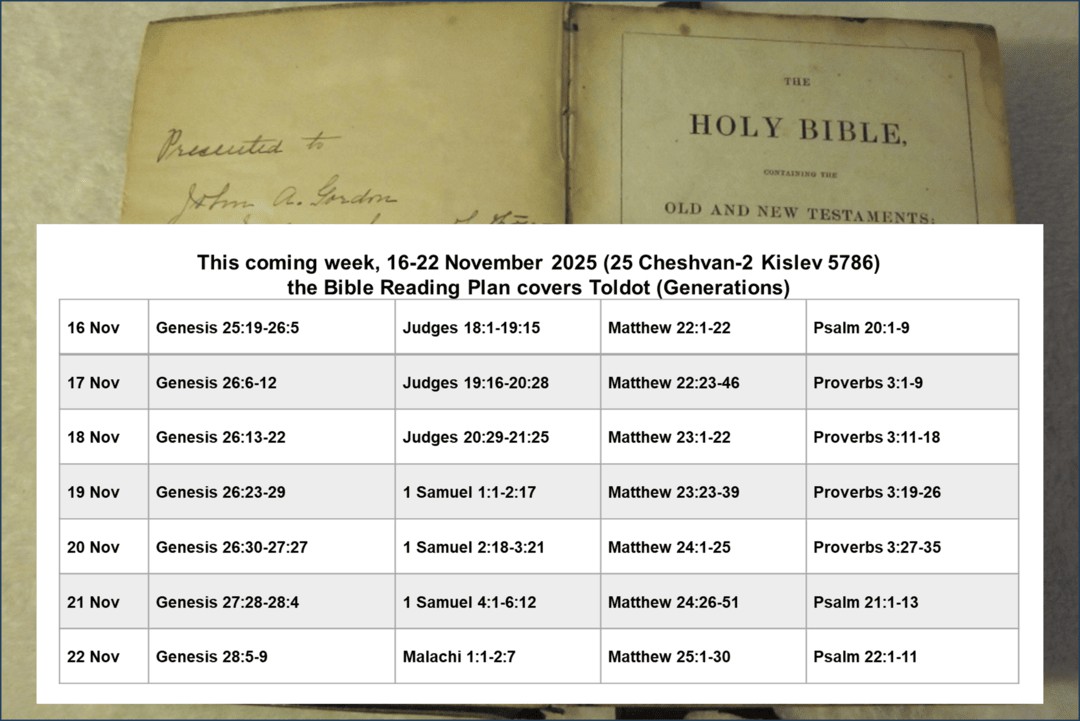

This coming week, 16-22 November 2025 (25 Cheshvan-2 Kislev 5786), the Bible reading plan covers Toldot (Generations).

https://thebarkingfox.com/2025..../11/14/weekly-bible-

In Luke 20:37-38, Jesus said that the title "God of Abraham" proves the resurrection of the dead because God is the God of the living, not the dead. However, Paul wrote in 1 Thessalonians 4:16 that the resurrection of the faithful is still to come.

How to reconcile these two statements?

In v38, Jesus said "All are alive to God," meaning, from God's perspective, all the righteous are alive today. But God's perspective isn't ours, as He sees the end from the beginning. Abraham, with all the faithful of every age, is alive today in God's eyes, whether or not he has already been resurrected today, because God isn't limited to a linear experience of time.

To YHWH, tomorrow is today.

https://www.americantorah.com/....2021/11/23/resurrect

111425 / 22nd day of the 8th month 5786

WORD FOR TODAY “can you walk blamelessly”: Luk 1:6 They were both righteous in the sight of God, walking blamelessly in all the commandments and requirements of the Lord.

WISDOM FOR TODAY: Pro 20:11 The character of even a child is known by how he acts, by whether his deeds are pure and right.

Ask the LORD how you can serve HIM better

www.BGMCTV.org

A new Edition of The

Lawful Literal Version

(AKA ‘Big Brain Bible’ BBB 🧠)

LLV Bible is out now!

…a work in progress with over 77,000 improvements so far!

The whole text of LLV364 The Petro Edition:

Gold nuggets in this edition: Often ‘the Petro’ REASON: so readers can see where the Greek text has it…

To stay informed of new editions of the LLV/BBB, click to enter chat here:

https://m.me/j/AbaDHuecyDKAutDi/

-

The LLV translation expands the marking found in some English Bibles (such as KJV, ASV) which italicise some of their words which are not literally translated from words in the source text but are added for the needs of English grammar, or to offer a clear interpretation where the text seems otherwise difficult to understand: (round brackets means it’s a Hebrew/Greek thing, that the sense of the enclosed words is understood to be implied by the grammar or syntax in the original language text), whereas [square brackets means it’s an English thing, that the enclose words that seem required by English, or that the words otherwise go beyond the original language text to offer a possible interpretation]. Also, underscores_joining_words_together indicate that these words are translated from a single word in the original language text. All these markings are presently inconsistent, so that there absence should not be taken to mean that they should not be there; the marking should become more complete in future editions, and words remaining in italics will instead be converted into (round bracket) or [square bracket] style.

e.g. Genesis 1:10: “And God called the dry land Earth; and (the) gathering_(together)_of the_waters he_had_called Seas. And God saw that [it was] good.”

1. (the) is implied in Hebrew by the ‘the’ in “the_waters” at the end of the Hebrew construct chain. Hebrew thus implies all nouns of the chain to be ‘definite’ (as though having ‘the’).

2. [it was] is not needed in the Hebrew syntax here, but English seems to require it.

3. he_had_called is translated from a single Hebrew word.

As far as the translator is aware, every name is now spelled with the aim of accurately reflecting the correct, historical pronunciations of these historical names according to modern phonetic English-alphabet transcription, e.g. ‘y’ not ‘j’ for the sound at the start of ‘yellow’, ‘w’ not ‘v’ for the sound at the start of ‘water’. The transcriptions in the LLV are aimed to be better than those of any English translation of Scripture made so far, because they consider not only the pointings of the medieval Hebrew texts but also the older transcriptions in Greek and Latin letters.

The LLV translation restores the Name YHWH (as ‘YAH__’) where it has been replaced by 'adonai, removes added occurrences of 'adonai, and where 'adonai is original, interprets it according to its original meaning, 'my_Lord'.

Please distribute freely, but only by sharing the link to this doc:

The LLV Bible is free, and now works online! Follow the steps here to get reading the Lawful Literal Version:

https://bit.ly/LLVBible

Please send suggestions for correction/improvement in private messages to Garth Grenache.

A list of all the improvements and the research and thinking behind them can be found at the same, above link.

Would you be pleased to like and follow this work here? https://www.facebook.com/LLVBible

And here:

https://m.me/j/AbaDHuecyDKAutDi/

Thought for Today: Friday November 14

Some years ago, one of my students asked me what had been my biggest surprise in life. I replied with: “the brevity of life”. Almost before we know it, the years have passed and life is almost over. On one hand, life’s brevity should challenge us. If ever we are to live for the Moshiach and share Him with others, it must be now. Yeshua said: “The night is coming when no-one can work” {John 9:4}. But life’s brevity should also comfort us. Life is short – and before us is eternity! Do not live as if this life will continue forever. It will not! Live each day with eternity in view.