Watch

Events

Articles

Market

More

Thought for Today: Shabbat November 29

There are many, many believers that lack assurance of their salvation. The key is to understand that the Moshiach took away all our sins – not part of them, but all of them. No matter how good we are, we cannot save ourselves, because YHVH’s standard is perfection. But the Moshiach, Who was without sin, did for us what we could never do for ourselves; He took all our sins on Himself, and took the death and hell we deserve. Depend solely on the Moshiach for your salvation. He paid the price – now you owe nothing!

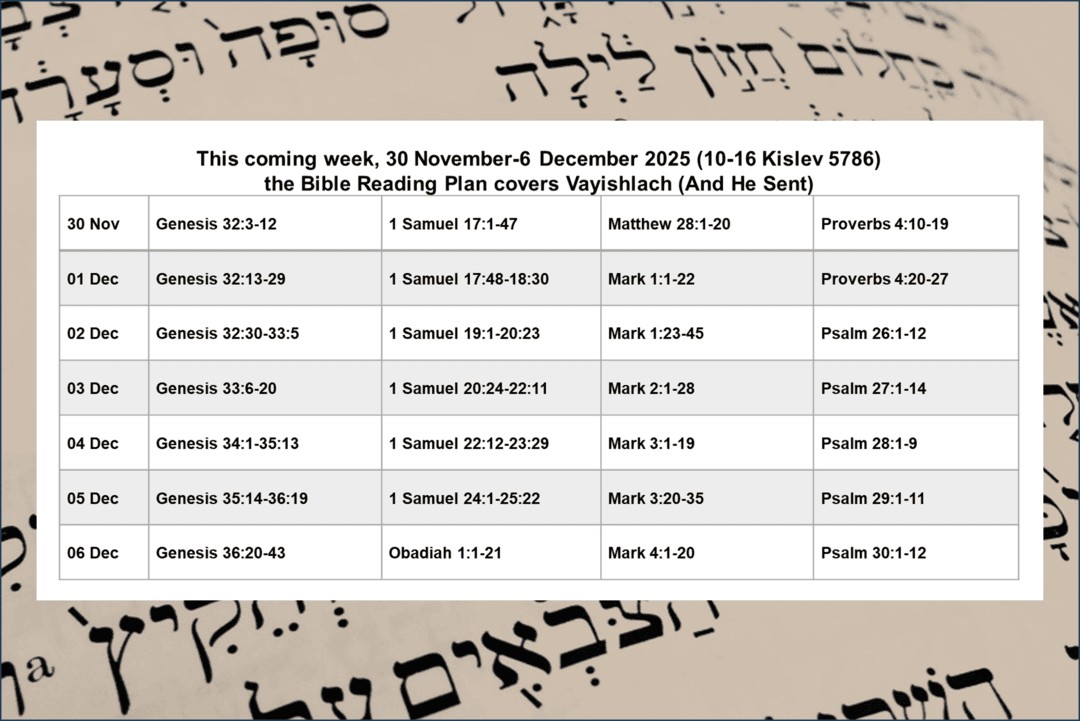

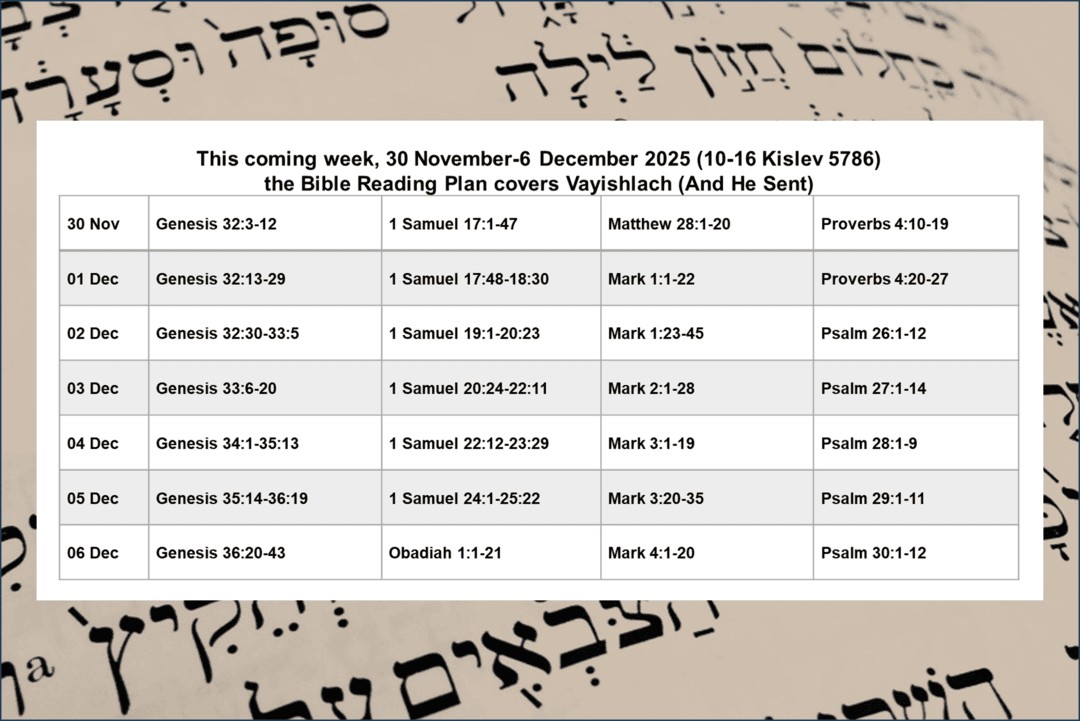

This coming week, 30 November-6 December 2025 (10-16 Kislev 5786), the Bible reading plan covers Vayishlach (And He Sent).

https://thebarkingfox.com/2025..../11/28/weekly-bible-

This coming week, 30 November-6 December 2025 (10-16 Kislev 5786), the Bible reading plan covers Vayishlach (And He Sent).

https://thebarkingfox.com/2025..../11/28/weekly-bible-

I have a new album coming out on all the streamers on Dec 10th. Currently, you can hear them on YouTube and YouTube Music.

https://youtube.com/playlist?l....ist=PLdf0VG55EbAmUBP

Here's First Fruits Ministries bulletin for tomorrow's Sabbath on 11/29/2025: https://firstfruits.cc/blog/20....25/11/28/sabbath-bul

Prepare your work outside; get everything ready for yourself in the field, and after that build your house.

Proverbs 24:27 ESV

Preparation for building a family involves learning wisdom and a trade, ensuring your ability to provide for your wife and children. What good is a house if you have nothing to eat?

See 1 Timothy 5:8. If you won't provide for your own family, you are worse than an unbeliever.

112825 / 6th day of the 9th month 5786

WORD FOR TODAY “do you have this level of faith”: Mat 8:10 Now when YESHUA heard this, He marveled and said to those who were following, "Truly I say to you, I have not found such great faith with anyone in Israel.

WISDOM FOR TODAY: Pro 19:20 Listen to counsel and accept discipline, That you may be wise the rest of your days.

Ask the LORD how you can serve HIM better

www.BGMCTV.org

Henk Wouters

we say it easy, we mean it hard.

let me bring you to jealousy.

what nick is saying is what the x-tians DO get.

Delete Comment

Are you sure that you want to delete this comment ?

Sarah

Delete Comment

Are you sure that you want to delete this comment ?